Partners involved in: Plymouth College of Art / Space*

When people think about digital fabrication the first thoughts that spring to their minds often include big open spaces full of high-tech-looking machines and people, noise and futuristic 3D-printed designs. The futuristic bit might sound far-fetched for some, but who would have thought that one day we would create and control processes that revolve around turning data into objects? As we continue to push the boundaries of what is possible within digital fabrication, the newest realisation has been brought to our attention through a once-in-a-century challenge that every single person around the world has been affected by – the Coronavirus pandemic. As we continue to learn how to live with and adapt to the ongoing situation, an emphasis on the need to teach these processes digitally has increased, as our familiar in-person tutorials and collaborative problem solving capabilities have become ill-suited to current restraints.

As the new year drew closer, we knew that our long awaited digital design and fabrication AYCH residency designed in partnership with Space* had to be rethought. In a pre-pandemic scenario, we would have had the privilege to host our partner’s participants in our college Fab Lab makerspaces, where they would experience the benefit of detailed components of fabrication as they followed the process of working with different machines. We had to deal with a question currently facing many other trainers across art, design, science, and engineering: how can we transform a hands-on making experience without access to the physical equipment, materials, and making spaces? As an extension of this, we were reminded that all digital fabrication machines, regardless of sophistication, impose constraints and limitations.

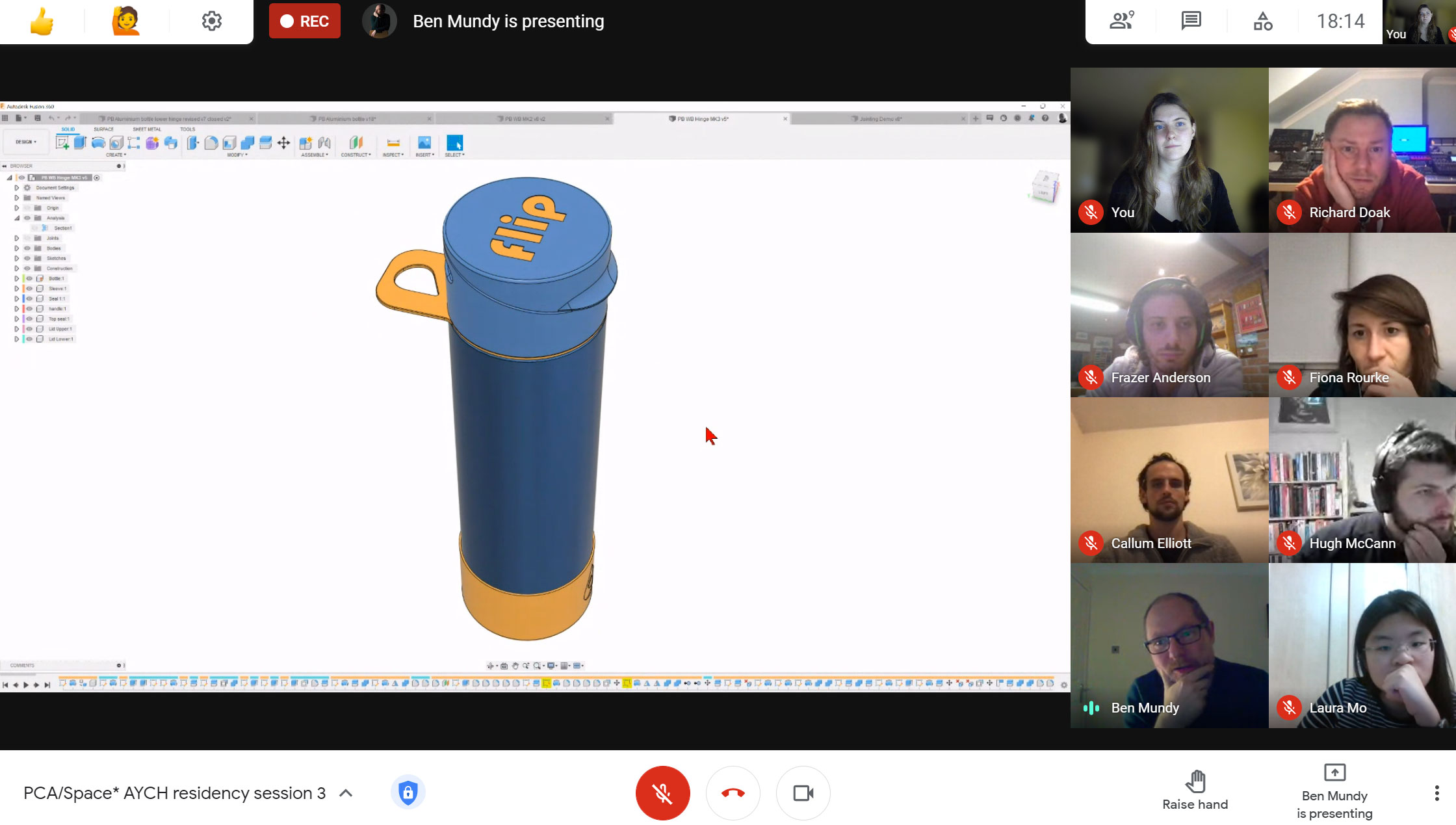

Producing successful digitally fabricated products requires learning how to design for these constraints. We saw it as an opportunity that enabled us to rethink something we deep inside knew was worth developing into something participants could still benefit from. This opportunity enabled us to bring a greater focus to software based learning and to restructure our residency programme from a model that relied on physical digital fabrication workshops, to more simplistic and personalised digital design and fabrication consultation sessions. By offering this tailored experience, we allowed participants to design the 5-week-long programme and residency sessions themselves, according to their needs and interests, which meant they were able to address specific questions and concerns that related to their own projects and designs. This flexibility also allowed us to adapt each residency session to be as suitable to each participant as possible, in addition to scheduling appropriate post-working day zoom meetings.

As a result, what this extraordinary challenge has taught us is that we can adapt in uncertain times and do what we do best – innovate. As our collective experiment with remote learning continues, it is our sincere hope that physical making classes will not disappear.

Yet, what we can celebrate is that with each challenge comes an opportunity and this particular moment in time has allowed us to explore these opportunities – increased inclusivity, improved accessibility, flexibility and interactivity.